My dad carried a folding lock blade knife in a leather case on his belt most of my younger years. He was a rural country minister by calling and a heavy equipment operator by necessity. The knife he carried had been given to him in the offering plate one Sunday by a gentleman who didn’t have any cash in his pocket at the time but had really been inspired by dad’s sermon that morning.

Dad considered that knife a blessing … and having a sharp knife can be just that. But carrying a dull knife can be a curse.

Making a knife sharp and keeping it that way is not a mystery … whether it be a kitchen, pocket, hunting or fillet blade. The skills are basic and can easily be mastered. There’s no need to spend a fortune buying some exotic sharpening stone imported from a third world country. All your knives can be sharpened to a razor edge and maintained that way using a basic sharpening, or whet, stone and a couple other items.

As a kid I was always amazed by some old guy who could take a little porous stone out of his pocket and with a little spit and a couple minutes of rubbing steel against stone he could hone a knife blade or pair of scissors to a fine edge. While dad always carried a knife, he exhibited no skills in keeping it properly sharp. His idea of sharpening a knife was giving it a few passes on the bench grinder, which was usually sufficient for the next time he needed to cut a piece of electrical wire or open a metal oil can.

With my first pocketknife, a small single blade, I began my five decade long lesson on how to obtain and maintain a proper sharp edge. While I may have been a slow learner myself, I can now sharpen and maintain all our knives in a few easy steps.

A side condition of my long-running desire to be able to sharpen a knife blade is that I’ve amassed a collection of stones, steels, specialty sharpeners, etc. But more about that later.

Nowadays, I divide my time between being a full-time real estate agent with an emphasis on rural properties, a part-time farmer who helps care for our small herd of cattle and pigs and just about as many tractors and related implements, a hobbyist rebuilder of antique tractors and cars and trucks in my workshop, and a hunter and angler every chance I get. Wherever I find myself, there’s always a pocket knife and usually some other blade close by ready to perform as needed. The keys are sharpen, straighten and strop.

SHARPEN

To properly shape the edge of any knife you need two things, a sharpening stone and a consistent angle. Some liquid – honing oil, food grade mineral oil, water, or even spit – added the stone will help carry away particles and keep the stone cleaner and speed the sharpening process.

Note here – There is a big community of people worldwide who take sharpening blades very serious. Those folks will have a lot of issues with the simplicity of this article. Some of their sharpening stone collections cost more than my relatively-new pickup truck. But this article is not for them. It’s for you, the man or woman who is using knives for everyday use and not making the sharpening process their life’s work or desire. Now back to the real reason we’re here.

You sharpen the blade by dragging it several passes over a whetstone. The trick is to hold the blade at the correct angle and maintain that same angle with every pass. If not, you’re simply randomly grinding material from your blade.

The correct angle for most paring and steak knives is about 12 degrees, and 22 degrees for thicker blades such as hunting knives or general-use pocket knife blades. I know some guys who prefer a finer angle on a pocketknife blade. Most of my pocketknives have at least two and sometimes three blades. I tend to sharpen one at about 15 degrees and the others to about 22 degrees.

You can buy an angle guide which helps position the blade against the stone. I have a couple of Work Sharp sharpening stones which came with a small wedge to help determine the correct desired angle. But I can tell you a nearly free way to accomplish the same thing.

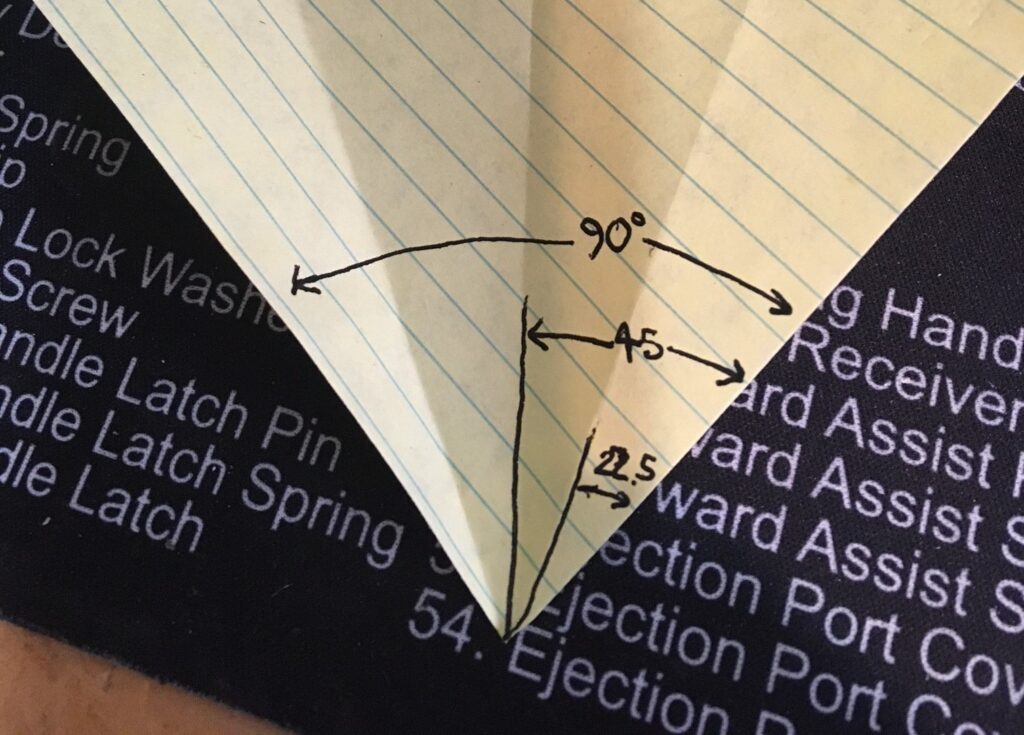

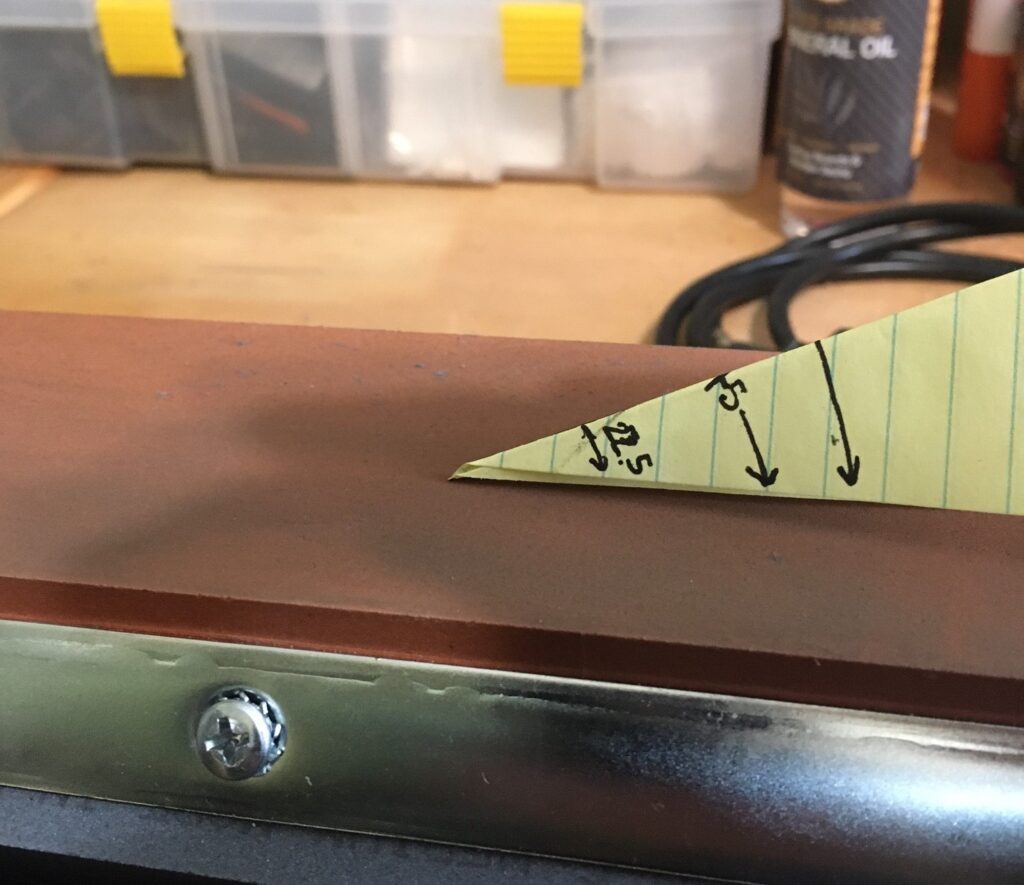

Find a Post-It note or other piece of paper with a square corner. Fold the corner in half, the way you used to when making a paper airplane as a kid … you remember! Now fold the paper again in the same manner. The first fold makes the original 90-degree angle of the paper now 45 degrees, and the second fold reduces that to 22.5 degrees. Sit one side of the angle flat on the sharpening stone, and the resulting angle sticking up is 22.5 degrees — ideal distance for holding the back edge of the blade away from the stone to assure a good hone. An additional fold makes the angle of the paper 11.25 degrees … ideal for thin-bladed kitchen paring knives.

Now rest the cutting edge of the knife against the stone near one end. Make sure the back edge, or spine, of the blade is the correct distance from the stone (22.5 degrees for blades meant for hunting, pocket carry and such, or about 11.25 degrees for kitchen and other precision blades) and make a pass across the stone as if you’re trying to slice a thin sliver from the stone. Repeat the move a half dozen times or more, then check the opposite side of the blade edge with the pads of your fingers for a noticeable bump of metal, called a “burr,” which has been created by the fine edge of the blade rolling over to the opposite side being sharpened. If you don’t feel a burr, continue on another dozen passes on the same side and check the blade again.

Once you feel a burr forming, turn the knife over and do the same to the other side, repeating the movements until the burr begins to form on the side you started with initially. Now, using a lighter pressure, repeat the process on the stone. Once the blade is sufficiently sharp using the stone it should move over the surface in a smooth motion with no noticeable burr.

A really dull knife can take 20 or 30 passes or more, while a fairly sharp knife can be honed in a dozen passes or less.

STEEL (Honing steel)

The truth is, most knives which appear to be dulled actually still have a suitable angle. A knife becomes dull when the microscopic fine point of the edge curls over, or buckles, during use. The metal is extremely thin and fragile at the sharpened edge, and even routine use cutting meat or slicing vegetables against a cutting board can cause that edge to curl and the knife to become noticeably less sharp over time. When that happens, the answer isn’t to grab the sharpening stone, but to grab the honing steel.

Like a suitable sharpening stone, a steel need not be expensive to be effective. A good general purpose honing steel will give a lifetime of service. And once you realize the significance that straightening a knife edge with a steel plays in keeping all your knives sharp, you’ll wonder how you ever got by without one. And if you’re like me, you’ll end up with a half dozen steels. There’s a reason that butchers often keep their steel attached to their belt or apron. I keep one on my sharpening and reloading table, one in the kitchen, one in my pickup truck, one in my workshop, a small one in a leather case that holds my Victorinox 6-inch boning knife used for butchering, and a smaller version in my tackle box with my fillet knife.

Under normal use a knife will not have to be sharpened but every few months or once a year. But a few quick passes over a honing steel will make that same knife cut true and clean with every use … all without removing steel from the blade.

Now that I’ve convinced you why, let’s quickly talk about how.

On television shows or at cooking demonstrations you often see the chef whip out his or her honing steel and point it to the heavens and quickly slap the blade down one side and then the other in an orchestrated solo of steel on steel. Those passes are made from near the tip of the steel back toward the handle. Fortunately, the handle has a wide guard where the handle meets the steel shaft to prevent the user from slicing their own hand in the process.

As an amateur sharpener I’m not comfortable with that way of honing. I prefer to hone away from my hand toward the tip. Either way is just as effective as long as you maintain the same angle on each side, with that angle being roughly the same angle you used when sharpening the blade on the stone. You’re ready to slice and dice again.

Remember, using a steel does not remove material from the blade, but instead lines up (or straightens) the microscopic edge which curls over with normal use and makes the blade dull. At this point the blade of your knife should be amazingly sharp.

STROP

For normal daily use the next step is unnecessary. However, if you want a blade which will shave hair, or be razor sharp for some other reason, the third and final step is to strop the blade.

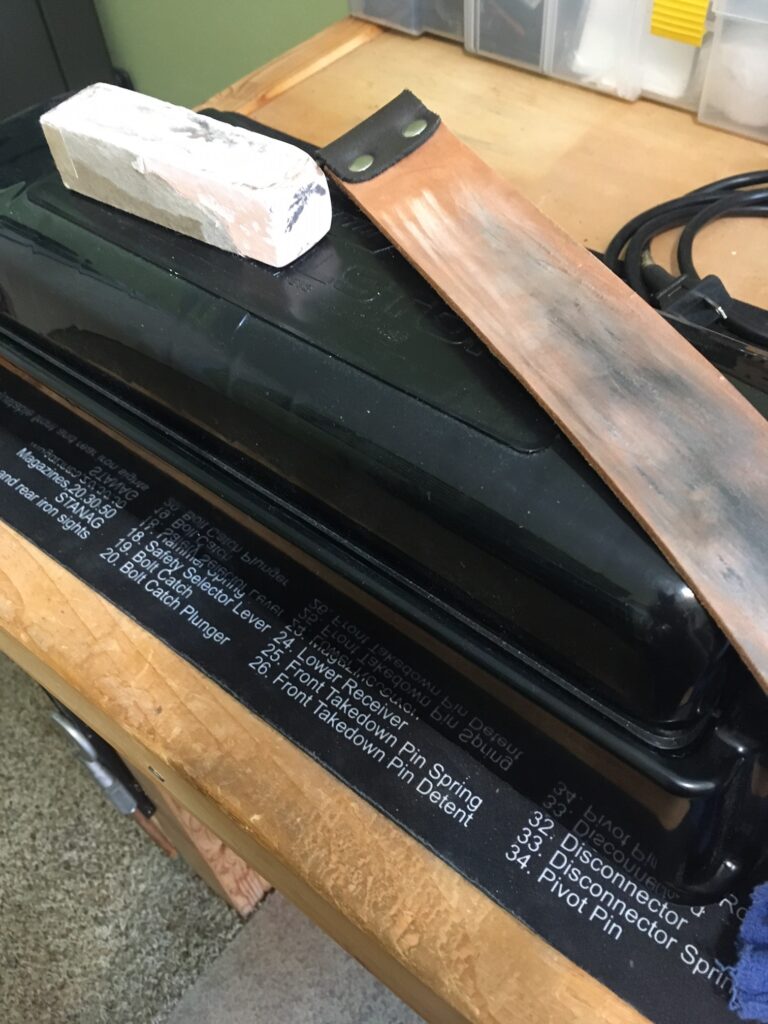

Stropping is often remembered as the move that grandpa or the barber did with a straight razor against a strip of leather just before shaving. That piece of leather often had rings or ties on the ends and was made for that purpose. But it also could have been an old leather belt or strip of leather adhered to a block of wood.

Unlike whetting with a stone or honing with a steel, with stropping you don’t make a cutting motion with the blade. Instead, you move the blade backward while maintaining a slight angle — which removes any unseen burrs and further straightens the by now nearly invisible fine edge of the blade.

A store-bought strop is a wonderful tool, which like a stone or steel, will last a lifetime. But as I said, you can also use a leather belt, knife sheath or clean leather boot as a makeshift strop.

Remember, stropping involves pulling, not pushing or cutting, the blade against the leather. It’s this final step that can take an extremely sharp edge to the point of razor sharpness. For an even better result, a strop can be improved with the application of a little stropping paste.

For kitchen, other household or workshop cutting, using a sharpening stone and steel is often enough. But for more precision blades, or if you enjoy sharpening and want to rid your forearms of all their hair, then adding a strop as a great final step.

A sharp knife is safer than a dull knife. With a sharp knife you have more control of where the blade edge goes. It will be cutting in and not deflecting as you try to slice through a fish, a side of beef, a piece of string or rope, or a big juicy tomato. You’ll need less force to get the work done. And it makes for a cleaner cut in the finished product.

If you live, or hang out very often, in rural settings you’ll find a use for a knife several times a day. It’s worth it to learn how to sharpen and maintain a blade.

When it comes to having a sharp knife, it’s not about the high price of the tools but the attention to the details that makes the difference when it’s time to butcher meat or cut vegetables, cut to length a piece of rope, or sharpen that stick.

Looking for a large tract of land where you can build, hunt and completely get away from any neighbors. Perhaps this more than 600 acres is what you’ve been looking for:

https://matrix.marismatrix.com/matrix/shared/jYtFksQg65Gd/4SimmsRd